This analysis compares our findings on the biological regulation of parental expression bias to those published by Perez et al (eLife 2015;4:e07860), who presented and applied the BRAIM model to RNA-seq data from the cerebellum of P8 and P60 hybrid mice.

Preparation

Load functions

source("~/projects/monoallelic-brain/src/import-data.R")

source("~/projects/monoallelic-brain/src/fit-glms.R")

source("~/projects/monoallelic-brain/src/graphics.R")

Orthology: matching human and mouse genes

Import “associated names” (symbols) for the selected human genes:

h.g.names <- unlist(read.csv("../../data/genes.regression.new", as.is = TRUE))

names(h.g.names) <- h.g.names

Import results by Perez et al provided in the first sheet of Supplementary file 1.

perez <- read.csv("../../data/elife-07860/elife-07860-supp1-v2.csv", as.is = TRUE)

Using AnnotationDbi

library(AnnotationDbi)

library("org.Hs.eg.db")

## Error in library("org.Hs.eg.db"): there is no package called 'org.Hs.eg.db'

library("org.Mm.eg.db")

## Error in library("org.Mm.eg.db"): there is no package called 'org.Mm.eg.db'

library("hom.Hs.inp.db")

An initial attempt with the AnnotationDbi::inpIDMapper function retrieved the id of only 3 mouse orthologs for the 30 selected genes. As a result of this frustrating result the following conversion hack was done. Mouse gene names were “humanified” by all-capitalization, i.e. using the rule: Mest (mouse) -> MEST (human). The detailed operations follow:

Convert for the 30 selected human genes the gene names (stored in h.g.names) into Ensemble gene ids. Then print the name of those genes for which the conversion failed.

human.eg.ids <- unlist(as.list(org.Hs.egSYMBOL2EG[mappedkeys(org.Hs.egSYMBOL2EG)])[h.g.names])

## Error in as.list(org.Hs.egSYMBOL2EG[mappedkeys(org.Hs.egSYMBOL2EG)]): object 'org.Hs.egSYMBOL2EG' not found

# the conversion failed for these genes:

names(h.g.names[! h.g.names %in% names(human.eg.ids)])

## Error in h.g.names %in% names(human.eg.ids): object 'human.eg.ids' not found

Import all mouse gene ids and symbols, do the conversion hack and check which human genes could not be converted:

# get all mouse genes

mouse.all <- as.list(org.Mm.egSYMBOL2EG[mappedkeys(org.Mm.egSYMBOL2EG)])

## Error in as.list(org.Mm.egSYMBOL2EG[mappedkeys(org.Mm.egSYMBOL2EG)]): object 'org.Mm.egSYMBOL2EG' not found

# "humanify" mouse gene names by all-capitalization, i.e. using the rule Mest (mouse) -> MEST (human)

names(mouse.all) <- toupper(names(mouse.all))

## Error in toupper(names(mouse.all)): object 'mouse.all' not found

# convert mouse gene names (i.e. symbols) to upper case and check for non-matching human gene symbols

names(h.g.names[! h.g.names %in% toupper(as.character(perez$gene_name))])

## [1] "TMEM261P1" "SNHG14" "AL132709.5" "RP11-909M7.3"

## [5] "ZIM2" "PWAR6" "FAM50B" "SNURF"

## [9] "KCNQ1OT1" "SNORD116-20" "RP13-487P22.1" "ZNF331"

## [13] "hsa-mir-335" "DIRAS3" "PWRN1" "NLRP2"

This result shows that 16 human genes could not be matched to any mouse ortholog. Below is a more principled and therefore more trusted approach using BioMart.

Using BioMart

This has been done with the web-based BioMart tool of Ensemble, which produced the following file

h2m <- read.csv("../../data/human-mouse-orthology.csv", as.is = TRUE)

str(h2m)

## 'data.frame': 37 obs. of 5 variables:

## $ Ensembl.Gene.ID : chr "ENSG00000162595" "ENSG00000145945" "ENSG00000106070" "ENSG00000167244" ...

## $ Mouse.Ensembl.Gene.ID : chr "" "ENSMUSG00000038246" "ENSMUSG00000020176" "ENSMUSG00000048583" ...

## $ Mouse.orthology.confidence..0.low..1.high.: int NA 1 1 1 1 1 NA 1 NA 1 ...

## $ Mouse.associated.gene.name : chr "" "Fam50b" "Grb10" "Igf2" ...

## $ Associated.Gene.Name : chr "DIRAS3" "FAM50B" "GRB10" "IGF2" ...

# remove rows without mouse ortholog; also remove the column "Mouse.orthology.confidence..0.low..1.high."

h2m <- h2m[h2m$Mouse.Ensembl.Gene.ID != "", -3]

nrow(h2m) == length(unique(h2m$Mouse.associated.gene.name))

## [1] TRUE

rownames(h2m) <- h2m$Mouse.associated.gene.name

h2m[-1 * 1:2]

## Mouse.associated.gene.name Associated.Gene.Name

## Fam50b Fam50b FAM50B

## Grb10 Grb10 GRB10

## Igf2 Igf2 IGF2

## Inpp5f Inpp5f INPP5F

## Kcnk9 Kcnk9 KCNK9

## Magel2 Magel2 MAGEL2

## Mest Mest MEST

## Nap1l5 Nap1l5 NAP1L5

## Ndn Ndn NDN

## Nlrp2 Nlrp2 NLRP2

## Peg10 Peg10 PEG10

## Peg3 Peg3 PEG3

## Snrpn Snrpn SNRPN

## Gm38393 Gm38393 SNURF

## Snurf Snurf SNURF

## Ube3a Ube3a UBE3A

## Zdbf2 Zdbf2 ZDBF2

Results

The results of Perez et al

Bringing the data table into a long format for plotting:

vname.pp <- paste0("posterior_mean.pp_", fc <- c("parent", "sex", "cross", "age"), "_effect")

vname.beta <- paste0("posterior_mean.", fc, "_effect")

perez.l <- # long format

reshape(perez[c("gene_name", vname.pp, vname.beta)], # extract variables of interest

v.names = c("P", "beta"),

direction = "long", varying = list(vname.pp, vname.beta), timevar = "predictor", times = fc, idvar = "id1")

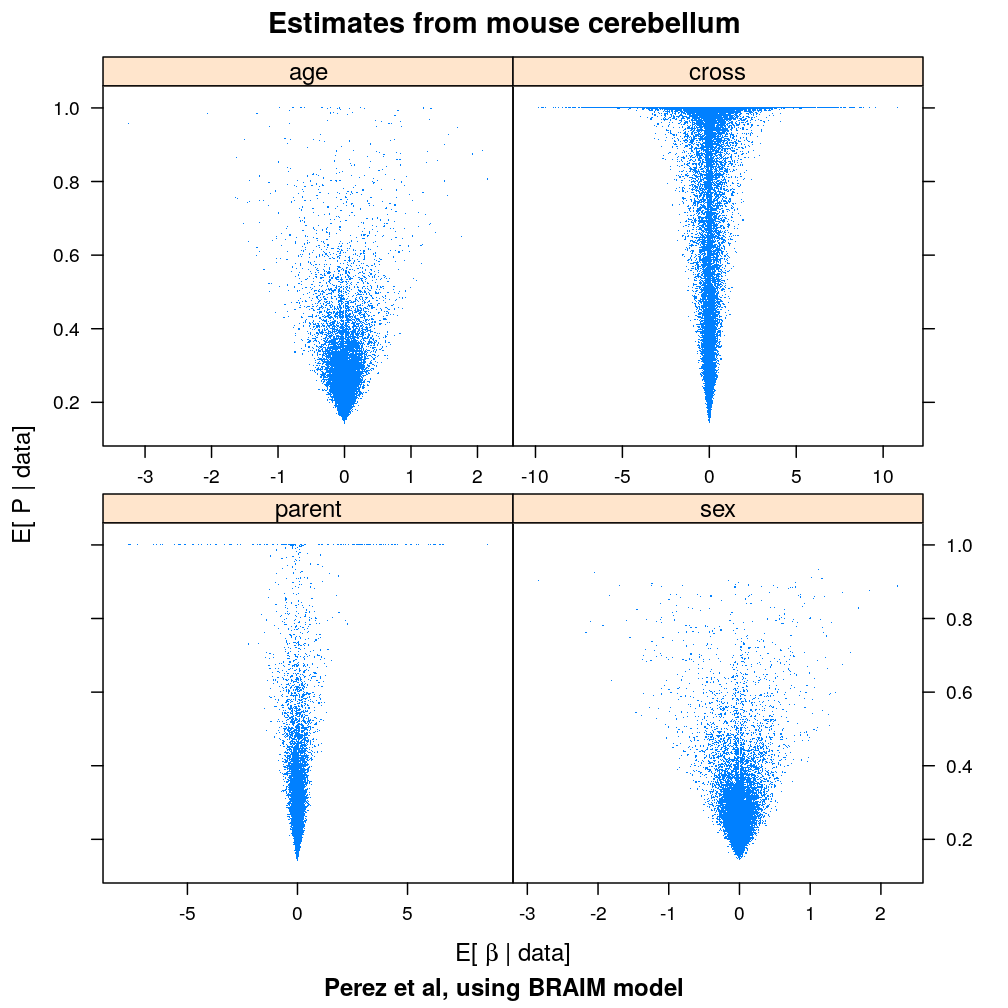

Plotted are posterior means of two parameters of the BRAIM model:

- βjg, the regression coefficient mediating the effect of predictor j for the parental bias of gene g; this is called

posterior_mean.age_effect,posterior_mean.sex_effect,…, in the first sheet of Supplementary file 1 provided by Perez et al. - Pjg, the probability that explanatory variable j has large effect on parental bias of g (i.e. induces a c× larger variance of βjg); this is called

posterior_mean.pp_age_effect,posterior_mean.pp_sex_effect,…,

xyplot(P ~ beta | predictor, data = perez.l, scales = list(x = list(relation = "free")), pch = ".",

xlab = expression(paste("E[ ", beta, " | data]")), ylab = "E[ P | data]",

sub = "Perez et al, using BRAIM model",

main = "Estimates from mouse cerebellum")

This plot shows that the posterior mean of a regression coefficient βjg need not differ greatly from zero even if Pjg≈1 provides a strong evidence that predictor j significantly influences gene g. This follows from the property of the BRAIM model that Pjg controls only the variance of βjg but not its mean.

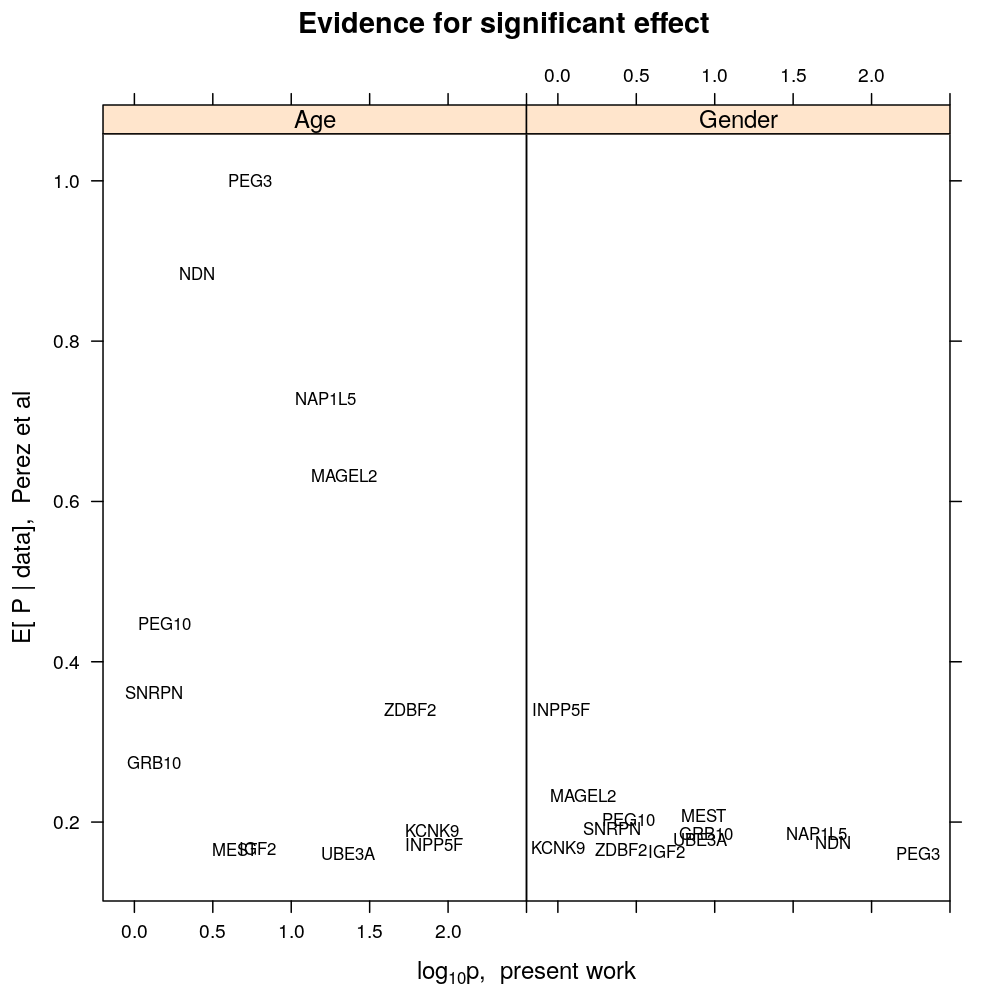

Comparison between the two studies

The following expressions focus only two predictors of parental bias: age and gender because only these two are clearly shared by our human study and the mouse study by Perez et al.

Data manuiplations

perez.s <- perez[perez$gene_name %in% h2m$Mouse.associated.gene.name, # rows: orthologs of selected human genes

c("gene_name", # informative columns

"posterior_mean.age_effect", "posterior_mean.pp_age_effect",

"posterior_mean.sex_effect", "posterior_mean.pp_sex_effect")]

perez.s <-

do.call(rbind,

lapply(unique(perez.s$gene_name),

function(n) {

df <- perez.s[ perez.s$gene_name == n, ]

cbind(data.frame(mouse.gene_name = n),

data.frame(t(as.matrix(apply(df[ , -1], 2, mean, na.rm = TRUE)))))

}))

perez.s$mouse.gene_name <- as.character(perez.s$mouse.gene_name)

rownames(perez.s) <- h2m[perez.s$mouse.gene_name, "Associated.Gene.Name"]

Combine evidence for the effect of age and gender from both our human study and the mouse study by Perez et al. The two types of evidence are:

- p-value for rejecting βjg=0 under the wnlm.Q or logi.S model, calculated either from normal distribution theory or a random permutation test

- the posterior mean E[Pjg∣data]

# Age

combined.a <- cbind(extractor("wnlm.Q", coef = "Age"),

extractor("logi.S")[-1 * c(1:2)])

combined.a <- cbind(combined.a,

expander("posterior_mean.age_effect", "beta.post.mean", df.long = combined.a),

expander("posterior_mean.pp_age_effect", "pp.post.mean", df.long = combined.a))

# Gender

combined.g <- cbind(extractor("wnlm.Q", coef = "GenderMale"),

extractor("logi.S")[-1 * c(1:2)])

combined.g <- cbind(combined.g,

expander("posterior_mean.sex_effect", "beta.post.mean", df.long = combined.g),

expander("posterior_mean.pp_sex_effect", "pp.post.mean", df.long = combined.g))

combined <- rbind(combined.a, combined.g)

The main result

Plotted below is E[Pjg∣data] from Perez et al against log10pjg, the p-value, from our study.

xyplot(pp.post.mean ~ - log10(p.val.t.dist.wnlm.Q) | Coefficient, data = combined, groups = Gene,

panel = function(x, y, ..., groups) {

panel.text(x, y, labels = groups, cex = 0.7, ...)

},

strip = strip.custom(factor.levels = c("Age", "Gender")),

xlim = c(-0.2, 2.5),

#aspect = 1,

main = "Evidence for significant effect",

xlab = expression(paste(log[10], p, ", present work")),

ylab = "E[ P | data], Perez et al"

)

Clearly, the evidence from the mouse and human study for any gene g do not match each other. While there is evidence for some genes from both studies that age has an effect, only our human study detected significant effect of gender. These results suggests large differences between the studies, which are methodological and/or biological in nature. In particular:

- the RNA-seq data is modeled differently so the interpretation of the E[Pjg∣data] (BRAIM) is not identical to pjg (wnlm.Q)

- differences in species, age window (relatively young mice vs relatively older people), and brain region

- differing measurement protocols